By Santa J. Bartholomew M.D. FAAP, FCCM & Betsy Kastak, DNP, RN, C-PNP

The organs of the digestive system, which are the intestines, large and small, the stomach, the pancreas, and the liver, are abdominal organs are separated from the chest cavity by a muscle known as the diaphragm. During development, both the diaphragm and abdominal wall may fail to form correctly, allowing the abdominal organs to extrude into the chest cavity in the first scenario or out of the abdominal cavity in the second.

There Are Four Types of Congenital Anomalies That Affect the Abdomen:

- Diaphragmatic hernia: organs push up into the chest cavity

- Exomphalos: organs project through the navel

- Gastroschisis: organs project through the abdominal wall

- Bladder exstrophy: the bladder projects outside of the abdominal wall.

These conditions may be diagnosed during pregnancy with ultrasound. Excessive amounts of amniotic fluid (polyhydramnios) can be a sign of these defects. The causes of these anomalies are unknown, so prevention is not possible.

Immediate Resuscitation in all of These Conditions

- The primary goal of immediate postnatal care in an infant with exposed abdominal contents is to avoid fluid loss (by evaporation) and hypothermia, as well as to prevent infection.

- An oral gastric tube should be inserted to keep the stomach emptied of air and fluid.

- Intravenous access is needed for IV fluids

- The baby may need to be sedated

- Prophylactic antibiotics should be given.

- The herniated contents of the abdomen are covered with warm saline-soaked gauze and the lower half of the newborn is placed in a plastic bag. Kinking of main vessels must be avoided, the optimal position is on the side in a lateral decubitus position. This is especially important if transport is required.

- If respiratory support is needed, continuous positive airway pressure or high-flow oxygen should be avoided to prevent filling the stomach and intestine with air. It is better to intubate. Ventilator support should only be applied if necessary.

Gastroschisis is a congenital anomaly in which the area surrounding the umbilicus is open which leads to extrusion of the bowel and occasionally other abdominal organs. Italian physician Cesare Taruffi first described gastroschisis in 1894. ‘Gastroschisis’ means ‘belly cleft.’ The reported prevalence varies from one in 3,000-8,000 live births. There has been an increasing trend demonstrated over the last few decades. This condition is more commonly seen in mothers of young maternal age and those of white Caucasian ethnicity.

- Simple gastroschisis is the bowel being outside the abdomen with no other obvious bowel problems, such as blockage or perforation.

- Complex gastroschisis occurs when there are apparent signs of a bowel blockage, a perforation, or an abdominal wall defect that has virtually closed compromising the perfusion of the bowel. Complex gastroschisis requires a surgical management plan that may include the formation of an ostomy and is related to a higher risk of surgical and medical complications.

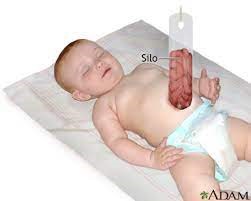

When the infant is born, staged reduction begins with a “silo” built at the bedside or in the operating room. In this technique, a silo is fashioned from a sheet of plastic or a modified saline bag and is sutured to the abdominal wall fascia (see figure 1). The bowels are contained in the silo and suspended over the abdomen. As time progresses, the bowel settles down into the abdomen. Reduction occurs over a period of days. Monitoring of bowel perfusion happens through the transparent material. The abdomen is then closed using steri-strips or sutures. The idea is that with gradual reduction of the bowel, the abdomen can slowly expand to accommodate the bowel without compromising expansion of the diaphragm and breathing or bowel perfusion. The advantage of the silo technique is that it can supplant the need for general anesthesia and reduce the risk of compartment syndrome of the abdomen.

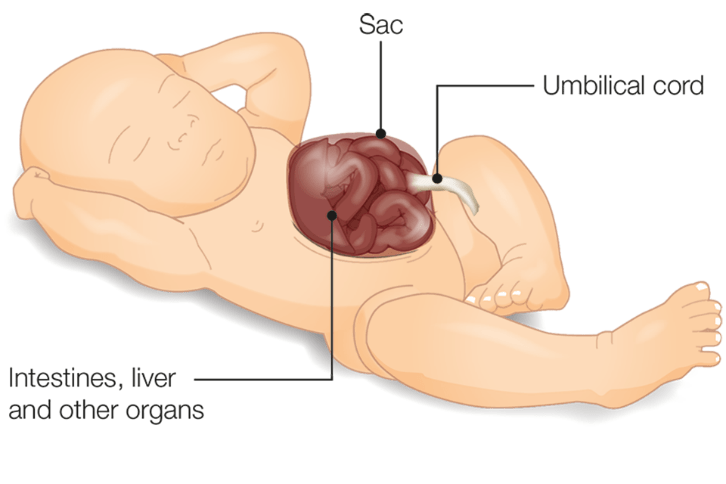

An omphalocele is similar to gastroschisis. It is a congenital anomaly in which the infant’s intestine or other abdominal organs extrude from the umbilicus. In an omphalocele, the small and large intestines are covered by tissue but can be seen easily. Between 25 and 40 percent of infants with an omphalocele have other congenital defects. Omphalocele is typically diagnosed prenatally by ultrasound. The birth of babies with gastroscisis and omphalocele requires planning, including Cesarean delivery at a center with a pediatric surgeon available.

Like gastroschisis, a sac is placed across the abdomen, which protects the abdominal contents and allows time for any other more pressing problems, if there are any, to be addressed first. In omphalocele, the thin layer of tissue is covered with a dressing stitched in place. Eventually, the abdominal contents will settle into the abdomen. When the omphalocele and organs can comfortably fit within the abdominal cavity, the synthetic material is removed, and the abdomen is closed.

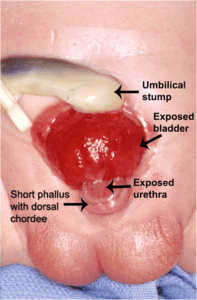

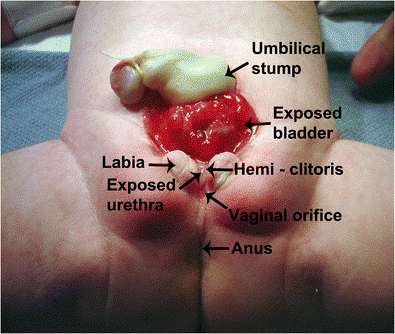

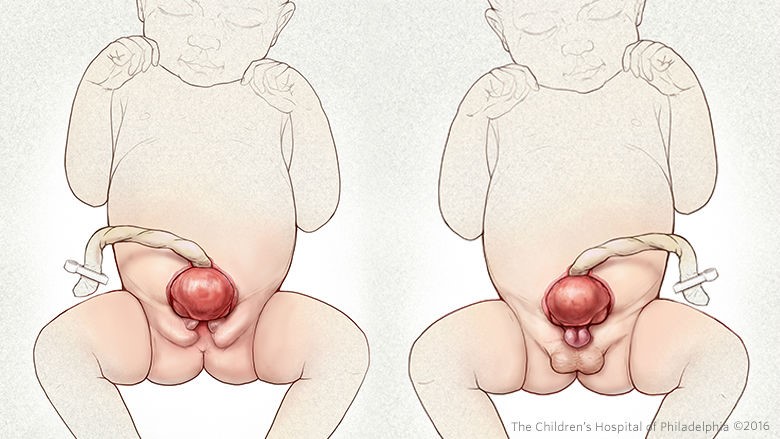

Bladder exstrophy is another condition where an error occurs in utero. This is where the bladder forms but remains outside the body (see figure 2). It is thought to happen at approximately 11 weeks gestation. Experts believe this defect occurs during the development of the lower abdominal wall. The developing muscles and pelvic bones are frequently affected too. Bladder exstrophy is typically found before birth during a routine ultrasound. This condition will be apparent when the baby is delivered, and the bladder is seen outside the baby’s belly.

If this condition is diagnosed before birth, the baby is often delivered so that a pediatric urologist can examine the newborn immediately. The urologist will note the size and quality of the bladder, the shape of the pelvis, and the anatomy of the sex organs, and a treatment plan will follow.

Bladder exstrophy is treated surgically. Surgical management depends on how severe the defect is. Working with a surgeon who is experienced with treating exstrophy is critical.

Treatment Goals

- Close the bladder, urethra, and pelvic frame.

- Rebuild a penis in boys that appears “normal” or rebuild the outer sex organs in girls.

- Fix the bladder so the child can maintain urine continence.

One form of treatment is “staged reconstruction,” This is several minor surgical interventions inclusive of each part of the above surgical procedures.

- The first surgery, which will close the bladder and pelvis, can wait a few months to allow the baby to grow.

- About six months after the bladder is closed, surgery is done to rebuild the urethra and/or penis.

- When the bladder has grown and potty training is imminent, surgery can be done to attain urinary continence.

When the bladder’s quality and penis size (for boys) is good at birth, closing the bladder and penile reconstruction can be done in a “single operation” early. Both early and staged reconstruction have good results. Continence is possible if the bladder has grown enough, nd the surgeon is skilled. Over time, further operations are often needed to improve the child’s ability to urinate. More surgery may also be required to rebuild and enhance the outer sex organs. In more challenging situations, longer-term management is needed. Modern reconstructive surgery can still allow a baby to complete all surgeries by the teen years.

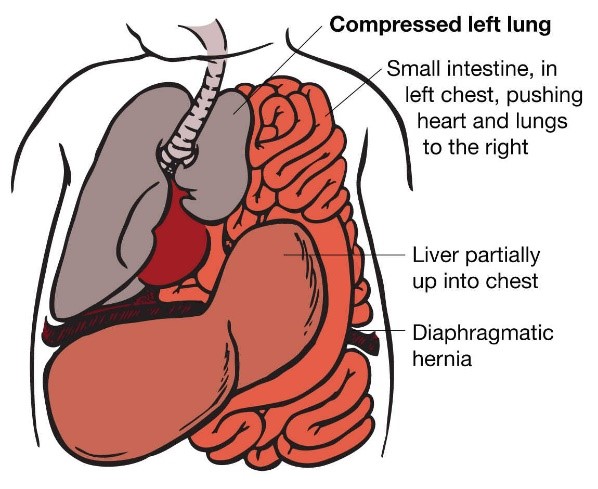

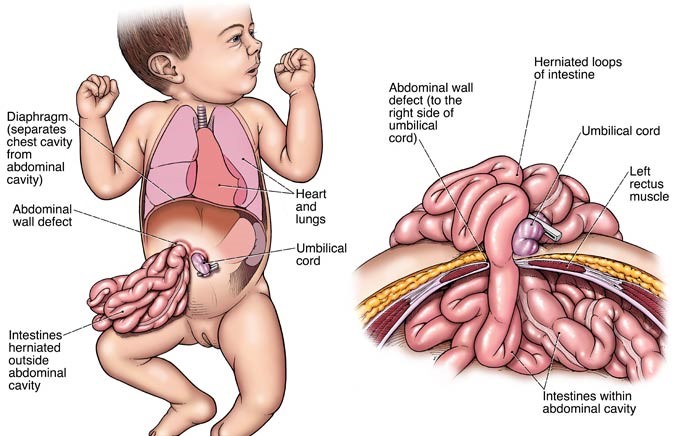

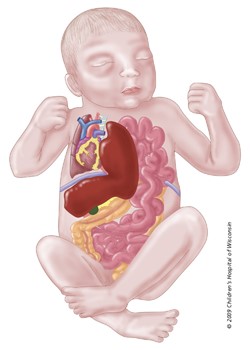

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is a genetic anomaly that happens when the diaphragm, a sheet-like muscle that crosses over the bottom of the ribcage, fails to develop correctly or close completely, separating the chest cavity from the abdominal cavity during fetal development.

The diaphragm separates the pleural cavity (where the lungs and heart are located) from the peritoneal or abdominal cavity (stomach, intestines, liver). It is the major muscle of breathing. A hole in the diaphragm allows abdominal organs to pass into the pleural cavity, which will cause the organs to compress the lungs and potentially prevent them from developing (see figure 3). Increased pressure in the lungs can cause decreased oxygenation in the body. Perfusion of the lungs is usually reduced, which may lead to pulmonary hypertension which can be a life-threatening complication of diaphragmatic hernia.

Currently, the outcome for babies with congenital diaphragmatic hernia continues to improve, with survival expected at 75-90%. CDH affects between 1-4/10,000 deliveries. In 80-85% of the cases, the hernia is on the left side of the fetus, and in 10-15%, it is on the right side of the chest cavity of the fetus.

Complications

- The most common complications observed in children after the repair of any abdominal wall defects are feeding difficulties, failure to thrive.

- Less common, chronic lung disease

- Neurodevelopmental and, motor delays often accompany abdominal wall defects.

- Children after abdominal wall repair also have a higher incidence of inguinal hernias later in development.

- Although rare, volvulus does occur after the repair of omphalocele specifically, in up to 3% of cases.

It is important to be aware of this possible complication in children presenting with acute abdominal pain and bilious vomiting after the repair of an omphalocele. Between 13–15% of patients present with adhesions in the small bowel with an accompanying obstruction.

References:

Abdelhafeez A.H., Schultz J.A., Ertl A., Cassidy L.D., Wagner A.J. (2015) The risk of volvulus in abdominal wall defects. J. Pediatr. Surg. 50:570–572.

Corey KM, Hornik CP, Laughon MM, et al. (2014) Frequency of anomalies and hospital outcomes in infants with gastroschisis and omphalocele. Early Human Development 90:421-4

Kelay A, Durkin N, Davenport M. (2016) Congenital anterior abdominal defects. Pediatric Surgery – II. Elsevier. pp264-66.

Matsagas M. (1995). Incidence, complications, and management of Meckel’s diverticulum. Arch Surg. 130(2):143.

Walter-Nicolet E, Rousseau V, Kieffer F, et al. (2009). Neonatal outcome of gastroschisis is mainly influenced by nutritional management. J Pediatric Gastroenterological Nutrition, 48:612-17.

Williamson S.W., Lawrence L., Suren Arul G., Rasiah S.V. Management and outcome for babies born with gastroschisis. Infant 2021; 17(1): 9–12.