By Santa J. Bartholomew M.D. FAAP, FCCM

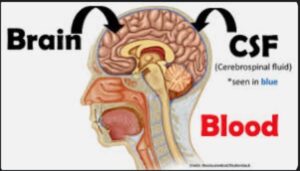

Increased intracranial pressure (ICP) is an increasing pressure inside your skull or cranium. The cranium is formed of bone, which does not allow for it to change in size. Inside the cranium are three components: the brain, cerebrospinal fluid, and blood. Any traumatic injury or medical condition that causes an increase in any of these components, will lead to an increased or elevated intracranial pressure.

As one component increases, it will cause a decrease in volume of one or both other components (known as the Monro-Kellie hypothesis). Elevated intracranial pressure may be acute due to a traumatic head/brain injury, or a more chronic process due to a brain tumor or other medical condition. Acute elevations in ICP require immediate medical attention while chronic increases allow for the body to compensate for the increases to a point and then these too require urgent attention.

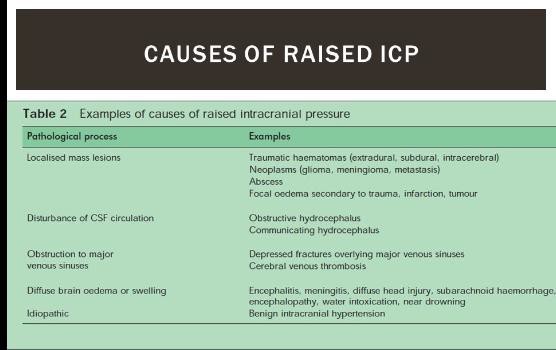

Causes of Elevated ICP

Elevated ICP may be due to a traumatic brain injury or another medical condition such as:

- Swelling (cerebral edema) of the brain

- Bleeding into the brain: intraparenchymal hemorrhage

- Bleeding around the brain: subarachnoid hemorrhage, subdural hemorrhage or epidural hemorrhage

- Brain tumor

- Hydrocephalus: This is an abnormal increase or volume of cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) from a tumor or from an abnormality in how spinal fluid moved through the brain (Chiari malformation).

- Infections: Encephalitis or meningitis,parasites

- Persistent and/or untreated high blood pressure

- Stroke: ischemic or hemorrhagic

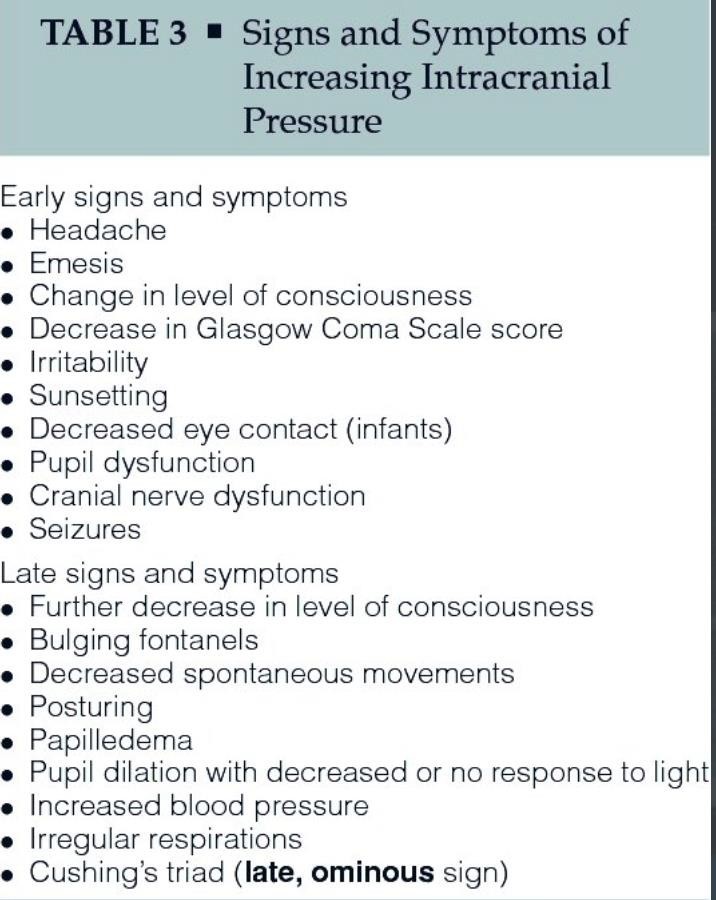

Symptoms

Elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) may present with a many variable symptoms. The most common symptoms of increased ICP are headache, confusion, and blurred vision. Additional symptoms may include:

- Vomiting (often a late sign)

- Rapidly increasing head circumference in babies

- High blood pressure

- Changes in personality or behavior

- Shallow breathing

- Increased fatigue/sleepiness

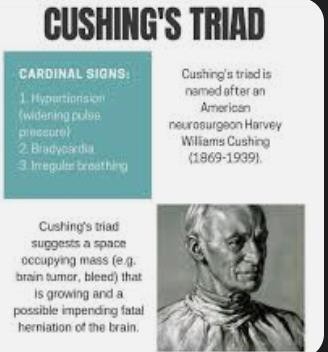

- Cushing’s Triad is a well-known triad but is often a late set of symptoms: HIGH BP, LOW HR, IRREGULAR BREATHING and portends the herniation of the brain through the hole that the spinal cord exits the skull (foramen magnum).

Elevated intracranial pressure can be a life-threatening condition. Emergent medical attention is crucial.

Diagnosis of Increased Intracranial Pressure

One of the most important components to diagnosing elevated intracranial pressure is a good medical history. It is vital for the healthcare provider to know any injuries and the mechanism of injury, how long an illness and how long symptoms have lasted and if they have progressed, what symptoms the patient has been experiencing, and any past medical history.

A thorough physical examination is also key to diagnosing elevated intracranial pressure. A physical examination focusing on the neurological system may include evaluation of the eyes with an ophthalmoscope which may show signs of elevated pressures (papilledema), and evaluation of the patient’s mental status. Any other abnormalities in the function of the crania nerves. Disturbances in the patients ability to walk or sit up. The healthcare provider will additionally be evaluating for any changes in the heart rate, blood pressure and respirations.

Additional tests that may be indicated to diagnose elevated intracranial pressure include:

- Lumbar puncture/Spinal tap: Performed by inserting a small catheter into the spinal cord, this test will measure the pressure of the cerebrospinal fluid. This is only done AFTER CT and ensuring that it is safe to remove any fluid from the spinal system with rare exception.

- Computed Tomography (CT scan): a radiologic study in which images of the head and brain are taken and signs of increased intracranial pressure (cerebral edema) are often seen such as effacement of the ventricles, smoothing of the gyri of the brain or loss of gray-white differentiation. In addition to signs of cerebral edema the CT scan may also give clues as to the reason for the cerebral edema (etiology) such as bleeding in or around the brain, brain tumor, or obstructions to flow of cerebral spinal fluid within the brain.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Using strong magnetic fields and radio waves, MRIs can provide very detailed images of the anatomy and physiological processes in the brain without the radiation the child is exposed to with CT scan. Although lack of radiation is appealing, MRI is long process that requires absolute stillness in the magnet and is often accompanied by the need for sedation in children, so CT is always the imaging of choice in emergencies.

With a severe head injury and/or life threatening elevated cranial pressures, the CT scan will provide vital information to the healthcare providers in a timely manner, allowing for immediate medical interventions.

Treatment of Elevated Intracranial Pressure

Elevated intracranial pressure is a medical emergency. Treatment is dependent upon factors such as severity of head injury, signs of herniation of the brain or if it process is a more chronic medical condition that has slowly led to an elevated intracranial pressure. Treatment may consist of the following:

- TREAT THE UNDERLYING CAUSE OF THE INCREASED INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE:

- Mechanical ventilation/Hyperventilation for management of carbon dioxide: decreasing cerebral blood flow and subsequently volume. This is only useful in acute emergencies and is not a long-term solution to increased intracranial pressure.

- Medications to reduce swelling such as hypertonic saline or mannitol.

- Elevation of the head of the bed to 30 degrees

- Sedatives/Analgesia

- Neuromuscular blockades (muscle relaxants resulting in medically induced paralysis)

- Hypothermia

- Control of all things and that increase the metabolic demand of the brain: seizures, fever, struggling against ventilation.

- Monitoring and Drainage systems:

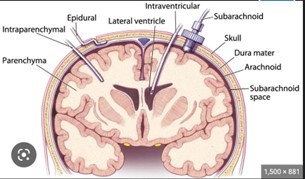

- Epidural Monitor: is placed between the skull and the Dural tissue: this can monitor pressure and is less risky from an infection standpoint as it does not enter the dura (the skin lining of the brain) but is not able to drain spinal fluid. The advantage is it is technically easy to place.

- Subarachnoid Monitor: again, relatively easy to place. Better monitoring data and less risk of infection but cannot drain fluid.

- Intraparenchymal Monitor gives very accurate information about the intracranial pressure but is in the brain parenchyma so has high risk of infection and does not allow fluid drainage. Is easier to place than and intraventricular catheter.

Intraventricular drainage catheter is the GOLD STANDARD for measuring ICP accurately and also can drain fluid to help manage severe increases in ICP that may be life0- threatening. It requires the skill set of a neurosurgeon and has the most risk of infection as this catheter transverses brain tissue and sits in the fluid filled lakes (ventricles) in the middle of the brain.

Complications of Increased Intracranial Pressure

Elevated intracranial pressure is a medical emergency and may have serious complications such as:

- Stroke

- Seizures

- Neurological/Brain damage

- Cushing’s Triad/Death: Death may result from herniation of the brain. Signs of impending herniation include Hypertension, Bradycardia (low heart rate) and irregular

It is important to seek medical attention immediately with any severe head injury or signs and symptoms of elevated intracranial pressure.

References:

Pinto, V. L., Tadi, P., & Adeyinka, A. (2022). Increased Intracranial Pressure. In StatPearls Publishing.

Dunn, Laurence T. “RAISED INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE.” Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, vol. 73, no. suppl 1, Sept. 2002, pp. i23–i27,

Kochanek, Patrick. “Management of Pediatric Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: 2019 Consensus and Guidelines-Based Algorithm for First and Second Tier Therapies.” Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, vol. 20, no. 3, Mar. 2019, pp. 269–279