By Santa J. Bartholomew M.D. FAAP, FCCM

Acute Abdominal Pain in Children: Necrotizing Enterocolitis

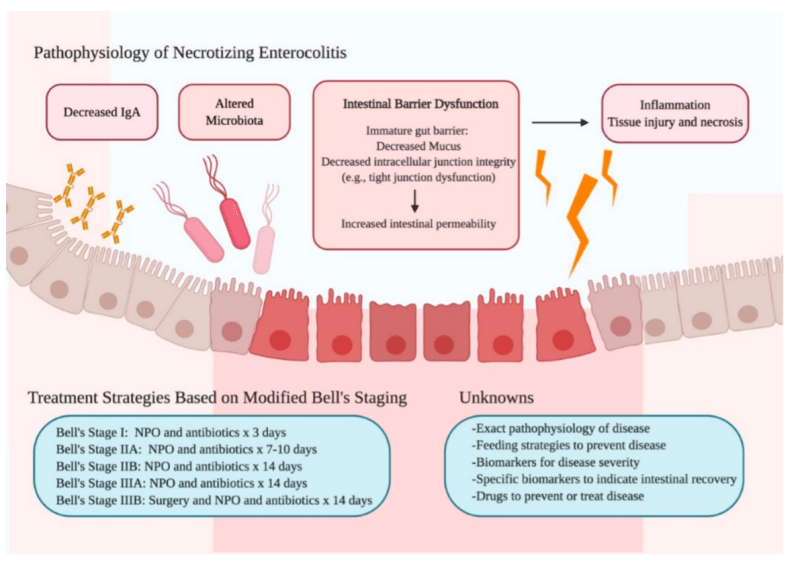

Necrotizing Enterocolitis is one of the most common GI emergencies in the newborn infant. Characterized by ischemic necrosis of the intestinal mucosa and associated with severe inflammation of the bowel. As gas forms in the bowel from gas producing organisms and bacteria these organisms can leak through the wall of the gut into the bloodstream causing severe sepsis, loss of large portions of bowel and death if not diagnosed and treated early.

Preterm infants: Incidence 2-7.5%

- More susceptible to GI injury because they lack GI defenses such as gastric acid, fully developed GI enzymes, normal mucous production because of incomplete maturity of villi, inadequate peristalsis and inadequate amounts of IgA.

- Acid and enzymes: eliminate most ingested pathogens and antigens from food

- Mucous inhibits the sticking of bacteria to the wall of the GI tract so it can cause inflammation.

- Active peristalsis prevents bacteria from forming complexes with antibodies from the infant that can be detrimental to the GI tract

- IgA reduces the risk of bacterial and viral antigens from penetrating the GI wall

Term Infants: Incidence 1-%

- Typically, these infants are eating formula not breast mill

- Have a preexisting condition or illness such as cyanotic heart disease or respiratory failure, perinatal asphyxia, sepsis of the newborn

This very quickly can become a fulminant process that requires one of more surgeries to remove dead bowel and risk the infant’s life and future ability to feed orally with all the consequent problems that go with the inability to eat by mouth.

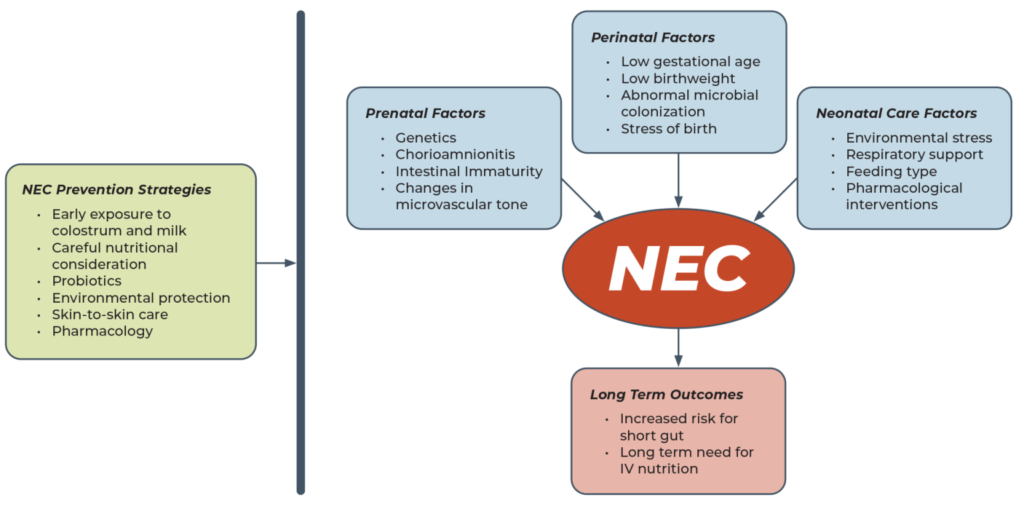

Risk Indicators

- Low gestational age

- Low birth weight

- Abnormal microbial colonization

- Intestinal prematurity

- Genetic predisposition

Other risk factors for NEC include

- Maternal issues such as drug use, infections of the uterus and fluid surrounding the infant (chorioamnionitis), HIV positive status of mother.

- Transition during delivery risk factors include: metabolic acidosis low flow or perfusion states where the infant does not get enough blood or oxygen during delivery such as tightly wrapped umbilical cord around neck, neonatal shock

Diagnosis

| STAGE | SYSTEMIC SIGNS | ABDOMINAL SIGNS | RADIOGRAPHIC | TREATMENT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IA Suspected | Temperature instability, apnea, bradycardia. lethargy | Gastric retention, abdominal distention, emesis, heme-positive stool | Normal or Intestinal dilation, mild ileus | NPO, antibiotics x 3 days |

| IB Suspected | Same as above | Grossly bloddy stool | Same as above | Same as IA |

| IIA Definite, Mildly ill | Same as above | Same as above, plus absent bowel sounds with or without abdominal tenderness | Intestinal dilation, ileus, pneumatosis intestinalis | NPO, antibiotics x 7 to 10 days |

| IIB Definite, Moderately ill | Same as above, plus mild metabolic acidosis and thrombocytopenia | Same as above, plus absent bowel sounds, definite tenderness with or without cellulitis or right lower quadrant mass | Same as IIA, plus ascites | NPO, antibiotics x 14 days |

| IIIA Advanced, Severely ill, intact bowel | Same as IIB, plus hypotension, bradycardia, severe apnea, combined respiratory and metabolic acidosis, DIC and neutropenia | Same as above, plus signs of peritonitis, marked tenderness, and abdominal distention | Same as IIA, plus ascites | NPO, antibiotics x 14 days, fluid resuscitation, inotropic support, ventilator therapy, paracentesis |

| IIIB Advanced, Severely ill, perforated bowel | Same as IIIA | Same as IIIA | Same as above, plus pneumoperitoneum | Same as IIA, plus surgery |

- Diagnostic signs: generally non-specific: abdominal distension and feeding intolerance, redness of the abdomen and induration or hardness of the abdominal wall, apnea or respiratory failure in infant, temperature instability, shock.

- Laboraotry signs: Low platelets and signs of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), 20% have + blood cultures.

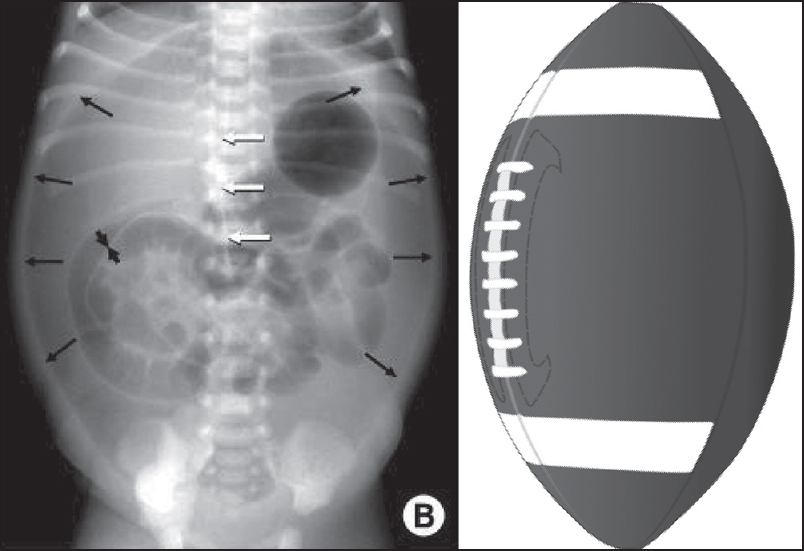

- Radiographic signs: Abnormal gas pattern, pneumotosis intestinalis (gas bubbles that appear in the wall of the bowel), air in the abdomen- a large amount causes a “football sign” – a large amount of air in the midline over the liver.

Football Sign

Pneumatosis Intestinalis

Gas in the venous system on the liver

Treatment

Treatment depends on presenting stage in the infant and disease progression but in general includes broad spectrum antibiotics, no feeding the gut (bowel rest), support of blood pressure with fluids and medications if needed., Surgery may be required to remove portions of dead bowel that put the infant at risk for ongoing infection and death.

NEC Prevention

Despite modern medicines myriad of antibiotics and radiographic tools adequate treatment that leaves the infant unscathed is still elusive. Research focus has been shifted to how to prevent this from occurring.

- There is early data that early exposure to mother’s colostrum (the first milk mother produces after infants’ birth) as high concentrations of immune mediators that provide protection from bacterial and stimulates the GI tract.

- Use of mother’s breast milk or banked breast milk decreases the incidence of NEC in infants. Even small amounts (trophic feeds) of breast milk in the infant’s gut helps nourish the villi that produce mucous, helps prevent injury of the bowel mucosa (lining) and helps prevent the gut wall from leaking bacteria into the baby’s blood stream.

- Environmental protection from stressors like cold stress and acidosis, excessive exposure to light and noise all provide decreased risk.

- Skin to Skin Care (SSC) enhances stress resiliency in infants, improves resting vagal tone (fewer bradycardic events).

- Use of probiotics in infants protects against inflammation and injury to the gut by proving “good bacteria”.

References:

Necrotizing enterocolitis: It’s not all in the gut. Alissa L Meister , Kim K Doheny, R Alberto Travagli. Experimental Biology and Medicine 2020; 245: 85–95.

Increased Fecal Calprotectin in Preterm Infants with Necrotizing Enterocolitis. Gokhan A, et.al. (Clin. Lab. 2012;58:1-4.

Nutrition in Necrotizing Enterocolitis and Following Intestinal Resection. Ou J, Courtney C, Steinberg A.E., Tecos M.E., Warner B.W. Nutrients 2020, 12(2), 520

Meister, Alissa L, Doheny, Kim K, Travagli R Alberto. Minireview: Necrotizing Enterocolitis: Its not all the Gut. Exp Bio Med 2020;245:85-95

Gokhan Aydemir, et.al. Increased Fecal Calprotectin in Preterm Infants with NEC. Clin Lab 2013;58.

Up-to Date: 2022: NEC : parts 1-5

Necrotizing enterocolitis: a Mini-review. Sanchez J.B., Kadrofske M. Neurogastroenterology and Motility 2019:31:3.